How Fluoride Was Discovered

I thought I would share a little dental history today. Like many of the medicines we have today, fluoride was stumbled upon by chance. The discovery of fluoride’s applications in dentistry trace back to the early 1900s when Frederick McKay, a dentist, noticed that many Colorado natives (~90% in one town) had significant brown staining on their teeth. This problem later became known as Colorado Brown Stain.

After observing these phenomena, he decided to invite another dentist, G.V. Black, to Colorado to collaborate with him on this unknown ailment, and through their research, they made two important discoveries:

- These brown stains were the result of development imperfections in tooth enamel. What we know now is fluorosis.

- Affected individuals had teeth that were surprisingly resistant to tooth decay.

McKay was later able to trace the source of this staining to the water supply, which was rich in fluoride due to significant natural fluoride deposits across the Western US.

It wasn’t until the 1940s that this knowledge was applied to strengthening teeth with the Grand Rapids water fluoridation study. During the 15-year project, researchers monitored the rate of tooth decay among Grand Rapids’ almost 30,000 schoolchildren. It was observed, around 11 years into the study, that the caries rate had decreased by 60 percent among Grand Rapids children born after water fluoridation began. Based on the success of this pilot study, states decided to move forward with public water fluoridation programs to reduce the incidence of tooth decay and improve oral health. Due to how the modern diet has evolved and the prevalence of acid-producing bacteria in society, fluoride has become essential to protect our teeth against daily wear and tear.

It is important to understand that, you don’t need to actually consume fluoride (via water, supplements, etc.) to receive the benefits. Water fluoridation programs, though still beneficial, are really a result of the original discovery and application of fluoride for public health. Through continued research, we have found that the protective qualities of fluoride are derived from its direct contact with tooth enamel, strengthening it and buffering it against acids. In fact, the topical application of fluoride from toothpaste and mouth rinses for example is more effective than systemic delivery.

Systemic delivery (drinking or eating it) also can produce some side effects at high doses (above what you would find in public water). Fluoride, like any mineral, can be bad for you if you consume too much.

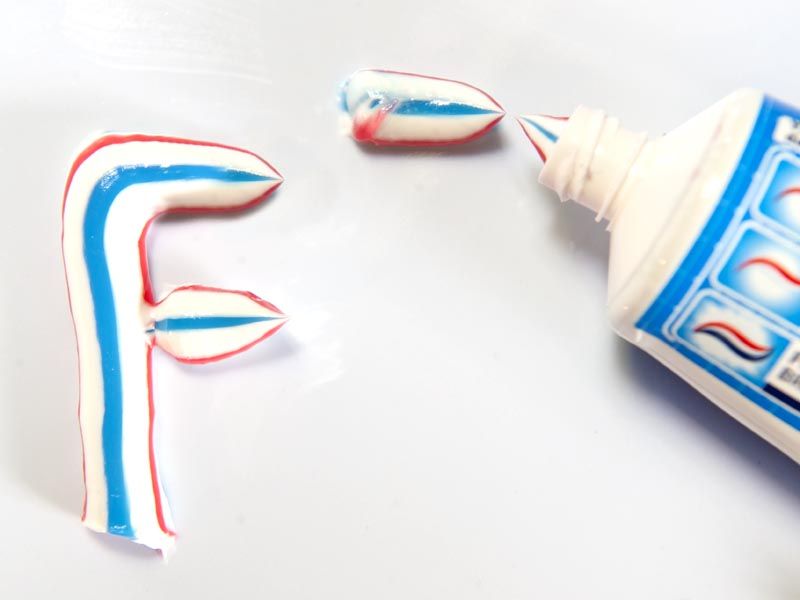

The most common side effect of excessive fluoride consumption is what originally drew attention to fluoride, brown staining, and developmental mottling of tooth enamel. This only occurs when too much fluoride is consumed while teeth are still developing. However, the reason why you’ll see a warning on any tube of toothpaste or bottle of mouthwash containing fluoride is that at extremely high levels, for instance, a small child drinking an entire bottle of mouthwash, fluoride can be toxic, making something like this is not a smart idea.